Capacity Building: A Comparison of Two Cases

By Patti Millar and Alison Doherty. Dr. Millar is an Assistant Professor at the University of Windsor in Windsor, Ontario and Dr. Doherty is a Professor at Western University in London, Ontario.

This research appeared in the July ’18 issue of the Journal of Sport Management.

Community sport organizations (CSOs) occupy an important place in the make-up of our communities by providing sport and physical recreation activities for all ages. CSOs, however, often face capacity-related challenges that can limit the impact that their programs have within their community. Organizations in this context have expressed challenges related to attracting and retaining volunteers, acquiring stable financial resources, and dedicating time to long-term planning.

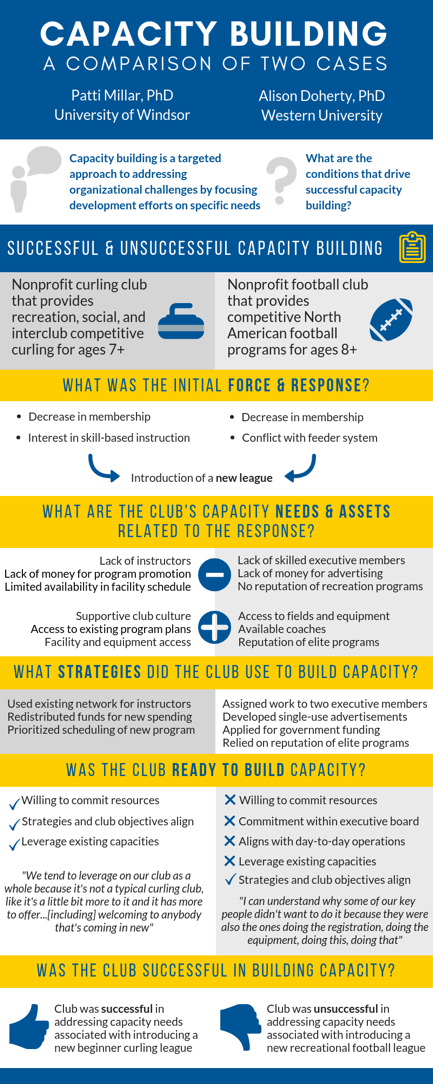

Building off our previous research, and given the growing popularity of capacity building as a priority in the non-profit sector (Bryan & Brown, 2015; Girginov, Peshin, & Belousov, 2017), we took a closer look at the process of capacity building in both an organization that was successful in its efforts, and one that was not (Millar & Doherty, 2018). We uncovered the forces, whether internal or external to the organization, that initiated capacity building, the clubs’ perceived ability to respond to that force and whether it had the capacity to do so. We also uncovered the clubs’ readiness to implement capacity building strategies, and ultimately the clubs’ success in building capacity and responding to the initial force. We present an infographic that summarizes the contexts and findings of the cases, illustrating their respective experiences with successful and unsuccessful capacity building.

We found that both organizations initiated the process in large part in an attempt to address declining membership; this acted as the force that ultimately drove the organizations to introduce new leagues in hopes that this would counter the low membership numbers.

Of particular interest, the findings show that an organization’s readiness for capacity building can be a key factor in whether or not their efforts are successful.

The curling club (successful case) had individuals within the organization who were willing to dedicate resources towards capacity building. It also identified areas of strength that could be leveraged during the capacity building process (e.g., relationships with local curling community). The club also reported that the capacity building strategies aligned well with its objectives, and therefore were less disruptive to operations.

The football club (unsuccessful case), on the other hand, despite an alignment between the capacity building strategies and the club’s objectives, expressed that a lack of willingness from the executive to plan and commit resources to capacity building was a key hindrance to the success of these efforts. The club also expressed that the added workload, and conflicts that arose as a result, combined with a lack of existing capacity, ultimately contributed to the failure of its capacity building efforts.

Together, these contrasting findings provide important considerations for organizations as they embark on the capacity building process:

Organizations are unlikely to build capacity simply for the sake of building capacity; there is some impetus that triggers the organization to react. Without recognition of that initial force, capacity building efforts will lack a strategic focus and are unlikely to be successful.

An assessment of capacity needs and assets should be conducted prior to implementing any capacity building strategies. These identified needs become the basis of the capacity building process, and so without a thorough assessment it is possible that an organization will overlook a critical capacity need. This also allows an organization to identify, upfront, capacity limitations that may hinder the process, as well as those assets that might be leveraged.

Perhaps most importantly, organizations should take the time needed to identify appropriate capacity building strategies that address their needs. These strategies should be ones that organizational members are willing to support, that are congruent with the organization’s processes, systems and culture, and that the organization has the capacity to implement. Without this readiness to build capacity, it is less likely that an organization will be successful in addressing its capacity needs.

The overarching finding from this study is that capacity building should be strategic in nature, such that the decisions made along the way are reflective of an organization’s mission, it’s internal and external environment, and should ultimately contribute to program and service delivery.

Interested in learning more about this research? Check out the article in the July 2018 Issue of the Journal of Sport Management.

References

Bryan, T.K., & Brown, C.H. (2015). The individual, group, organizational, and community outcomes of capacity-building programs in human service nonprofit organizations: Implications for theory and practice. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 39, 426-443.

Girginov, V., Peshin, N., & Belousov, L. (2017). Leveraging mega events for capacity building in voluntary sport organizations. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 28, 2081-2102.

Millar, P., & Doherty, A. (2016). Capacity building in nonprofit sport organizations: Development of a process model. Sport Management Review, 19, 365-377.